Safeguarding Earth’s Biodiversity by Creating a Lunar Repository

As more plants and animals are threatened with extinction, Smithsonian scientists are exploring a radical effort to preserve and safeguard biological samples from important and at-risk species on the surface of the Moon.

Earth is in a biodiversity crisis. Human-caused factors, such as global warming and habitat degradation, continue to threaten countless species with loss and extinction. This loss is part of a long-term trend that may be accelerating faster than our ability to save these species in their natural environments.

In the face of this potential catastrophic loss, scientists ask: are there innovative ways to conserve and protect species, and how can we protect biodiversity in the event of a major disaster on Earth?

A group of Smithsonian scientists and other researchers envision a lunar biorepository — a vault of biological samples that could preserve genetic material indefinitely on the Moon. This method would allow scientists to passively store valuable samples of live cells by harnessing the unique features on an off-world site.

How does freezing animal cells help conservation?

The Smithsonian Institution is a leader in using advanced technology to save species and ecosystems. One method is cryopreservation: by harnessing extreme cold, biological materials (such as sperm, cells, and embryos) can be placed in a state where they are alive yet frozen, and able to be thawed out for future use. Although new, frozen cell repositories are already being used in the Smithsonian’s conservation efforts.

The proposed lunar biorepository draws on existing plans to safeguard Earth’s biodiversity in a ‘backup’ location. This was inspired by an international consortium of scientists who established a facility near the Arctic Circle that holds and protects copies of Earth’s rare plant seeds in an energy-free, bomb-proof shelter. The Svalbard Global Seed Vault, opened in 2008, may prove invaluable for reseeding the planet after a global disaster.

Why do we need a biorepository on the Moon?

Although there are many thousands of biological samples currently stored on Earth and used in conservation efforts, storage of these samples requires active maintenance via specialized freezers and other high-tech equipment that could potentially fail in the event of an emergency, a natural disaster, or even a loss of electricity.

The Moon may seem like an unlikely place for long-term storage of biological samples like cells, sperm, and embryos, but Earth’s natural satellite offers several distinct advantages for biopreservation that are not found anywhere on our planet.

- The Moon is much colder than Earth. There are existing craters and deep canyons on the Moon’s surface that are permanently shadowed from the Sun’s warming rays. These areas sustain temperatures as low as -196° Celsius—the same temperature as liquid nitrogen, which is used to store cryopreserved samples on Earth.

- Constantly cold temperatures mean samples can be kept with little to no human intervention.

- Burying samples a few meters belowground would shield the samples from radiation and damage from space debris.

- If placed in these extreme cold spots, active refrigeration would not be needed, and the biological samples could be stored indefinitely with minimal to no resources.

- At approximately 238,000 miles (384,000 kilometers) from Earth, the Moon is protected from any unpredictable natural and/or geopolitical disasters that may befall our planet.

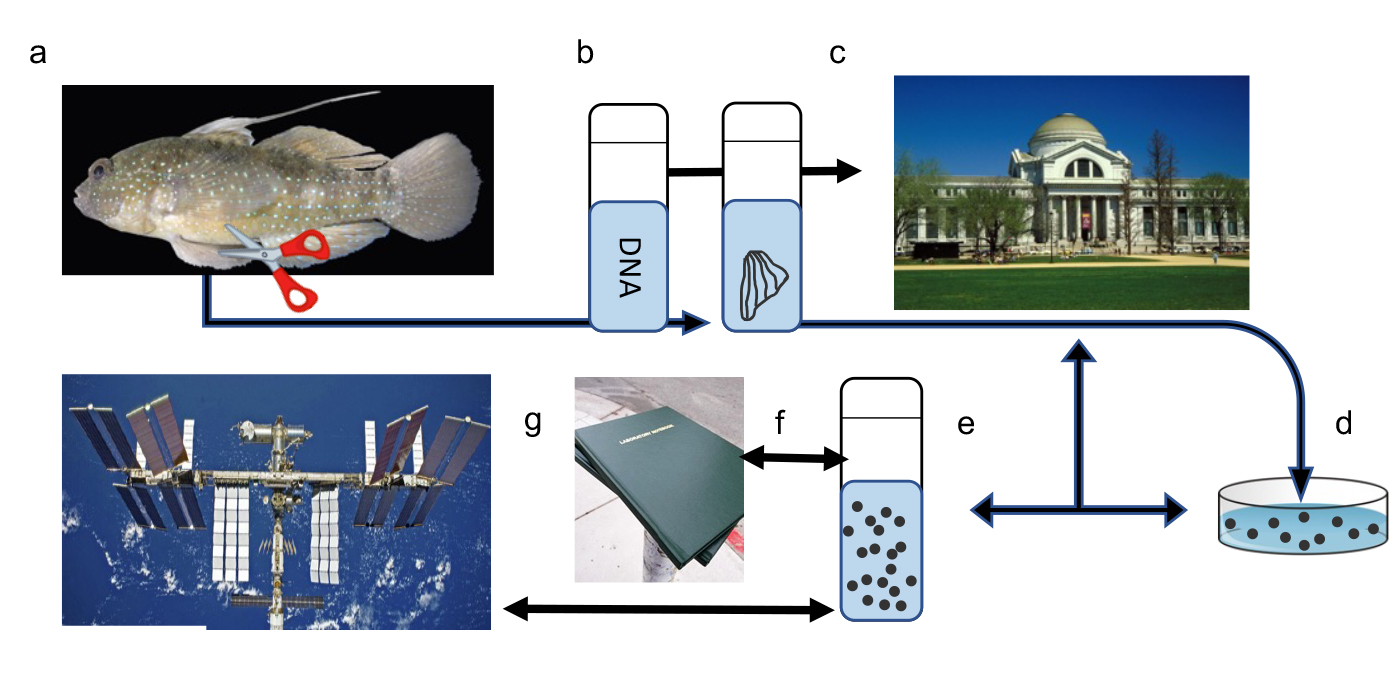

A scientific flow diagram detailing steps involved for cryopreserving cells and testing them in space. a.) Sampling of pelvic fins from the starry goby. b.) Fins and DNA samples are stored in a biorepository. Fins may be placed dry in a cryovial with a sterile damp sponge and cells later expanded into fibroblasts or cryopreserved and held in a biorepository. c.) Earth biorepository, such as the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, where cryopreserved samples may be held for extended periods prior to launching into space. d.) Fibroblasts from fins expanded in the lab. e.) Fibroblast cells cryopreserved. f.) Cryopreserved cells and cryo-packaging tested on Earth for robustness under space conditions. g.) Space-ready cryopreserved samples are sent to the International Space Station for testing, and then returned to Earth for analysis of viability and changes to DNA.

What life groups might be included in a lunar biorepository?

Although there would be value in preserving samples from all the Earth’s approximately 8.2 million life forms, the proposed plan would start with the species that will be most affected by climate change in the next 50 years. Beyond that, a list of potential candidates might include groups such as:

- Ecological engineers

- Pollinators

- Extreme environment fauna

- Primary producers

- Temperate to cold-water fishes

- Threatened and endangered animals

- Organisms important in space exploration

- Wild relatives of domesticated organisms

- Species of cultural importance

Who is involved?

Dozens of scientists and researchers have already contributed to this project, including the Smithsonian Institution’s Mary Hagedorn, Pierre Comizzoli, Lynne Parenti, Bob Craddock; University of Minnesota’s John Bischof and Susan Wolf; National Ecological Observatory Network’s Paula Mabee; University Corporation for Atmospheric Research’s Bonnie Meinke; University of Washington’s Baptiste Journaux; and Harvard University’s Shannon Tessier, Rebecca Sandlin, and Mehmet Toner.