Monitoring Meadowlark Movements

At first glance, Virginia’s farmlands seem quite peaceful. But beneath the swaying fields of hay lies a bustling ecosystem for the birds that call the grasslands home.

One such avian animal—the eastern meadowlark—is key to the health of its habitat.

Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) scientists are monitoring meadowlark movements—all for the cause of conservation. Learn more about this study from Amy Johnson, program director of SCBI's Virginia Working Landscapes.

What inspired you to study eastern meadowlarks?

I have spent the last decade studying grassland birds in Virginia, and I have to say eastern meadowlarks quickly rose to the top as one of my favorites. For starters, they are one of the first grassland birds to start singing in the spring. Hearing that melodious “spring of the year” whistle as it echoes across a field is a welcome sign that winter is over. Their nests are also amazingly intricate; they can take up to eight days to build and are constructed entirely by the female!

This species is a true icon of our eastern farmland—a landscape cherished by so many, yet one that sees the impact of suburban development. The meadowlarks are what we call “a common bird in steep decline”—which means that although their populations have plummeted by almost 90 percent since 1966, their numbers are not yet low enough to warrant a threatened or endangered status.

Studying the movements of these birds will give us a unique opportunity to learn how they use and interact with their habitat. In turn, this will help us develop conservation strategies to protect the areas where the birds live before it is too late to turn their numbers around. Doing so has the potential to benefit a vast array of other species that share the same landscape, like bobwhite quail and pollinators.

Hay is harvested at a field in Virginia.

What role do they play in the ecosystem?

Like many insectivorous species, eastern meadowlarks provide an important ecosystem service by consuming mass amounts of insects. In fact, insects make up nearly 75 percent of their diet!

Aside from that, our regional bird populations act as key indicators of the overall health of our ecosystem. Annual bird counts, like the North American Breeding Bird Survey, have given research scientists like myself one of the most well-documented, complex and long-term datasets of wildlife populations known to science. When meadowlarks and other key grassland species decline, that is a sign their ecosystems—which we humans share—are also in trouble. I think of them like the canary in the coalmine.

Smithsonian scientists place a GPS tracking device on an eastern meadowlark.

How will you track the eastern meadowlarks?

Our colleagues at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center and Movement of Life Initiative have a phenomenal track record for elucidating migratory patterns of species using satellite tags and geolocators. We are using methods that have already proven successful on other species around the globe. For this study, we are using tiny GPS tags that enable us to download their locations online through satellite technology. Each device weighs less than 4 grams!

Given that meadowlark populations fall almost entirely on private lands, this project will require strong support and participation from our local farmers. Fortunately, we have a committed network of private landowners through the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s Virginia Working Landscapes program. We are excited to work with them to move this project forward.

Eastern meadowlark in Virginia.

How can individuals help grassland birds?

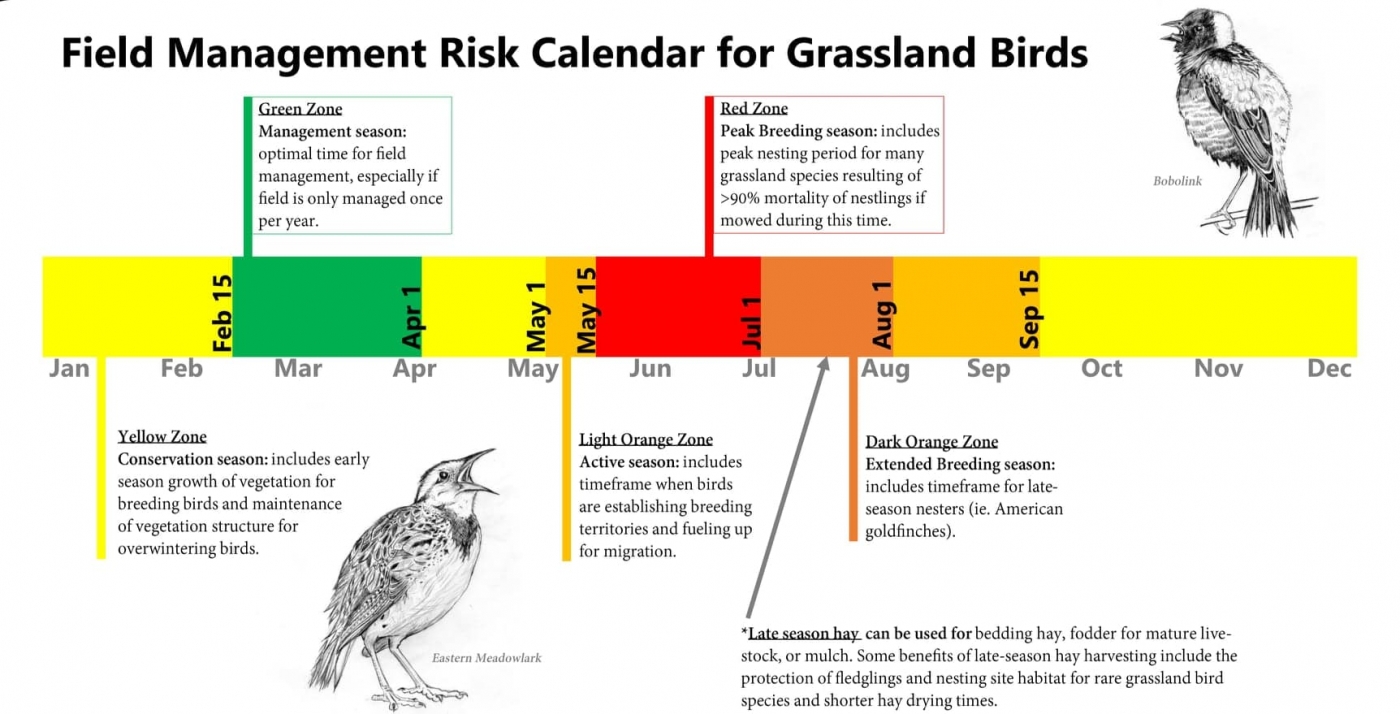

One of the biggest threats facing meadowlarks and other grassland birds is the timing of hay harvest, which often coincides with peak nesting season. Researchers in the northeastern U.S. found that when fields were harvested during nesting season, it resulted in 94 percent mortality of grassland bird nestlings.

To help mitigate this, Virginia Working Landscapes has put together a guide for landowners with recommendations for managing their fields while conserving the native birds and pollinators that live there.

To conserve eastern meadowlarks and other grassland birds, Virginia Working Landscapes developed a "risk calendar" to help local landowners plan the maintenance of their properties such that native species can thrive.

What makes you optimistic about this study?

In addition to working with Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center and Movement of Life scientists to gain new information on meadowlark migratory connectivity, I look forward to including landowners in Smithsonian research. Building on existing community partnerships will enable us to improve our understanding of what these animals need to thrive and help us make strides to conserve the birds’ breeding and wintering grounds.

Over 95 percent of the eastern meadowlark population resides on private lands, so the best hope for their future lies in the hands of private landowners. There are agricultural practices that are compatible with the needs of meadowlarks and other grassland birds. By working together on this project, we can provide landowners with the tools they need to optimize management practices for conserving eastern meadowlarks and other grassland species in perpetuity.

This story appears in the July 2019 issue of Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute News. Friends of the National Zoo and Conservation Nation provided funding for this project.