House Hunters: Amazing Arthropods

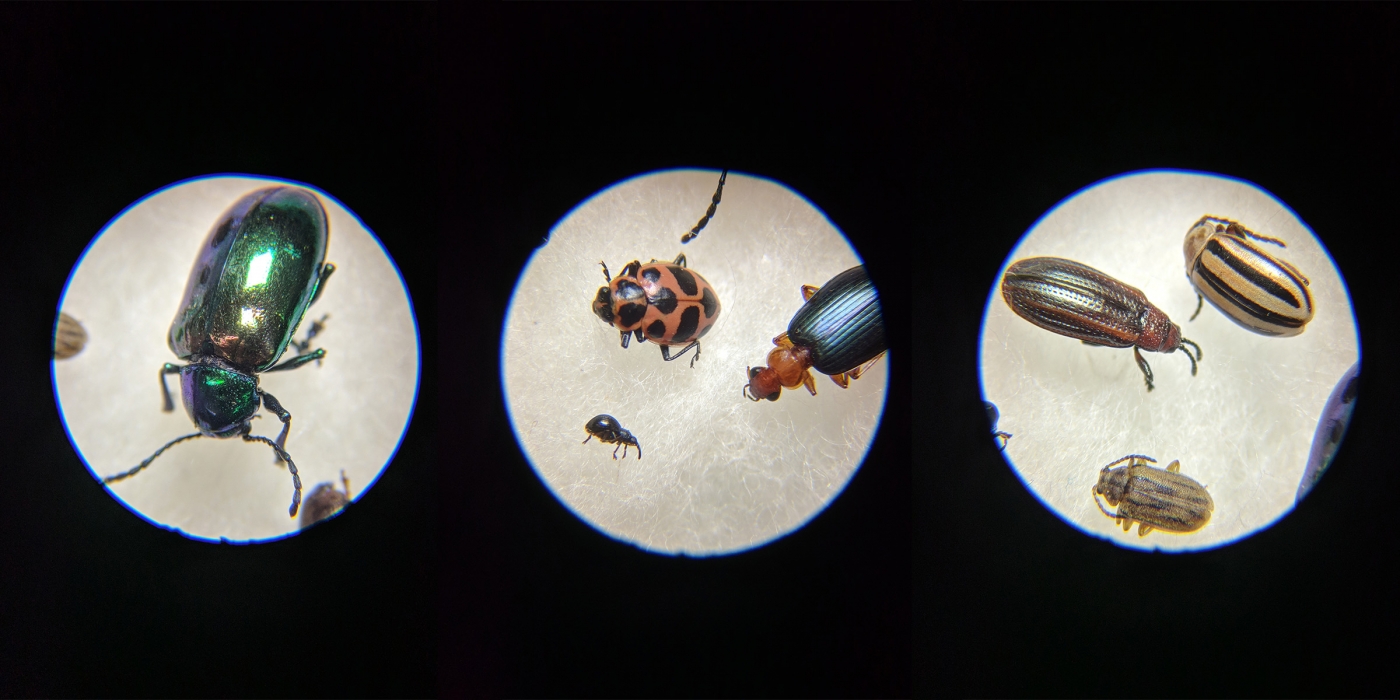

Many creatures, great and small, call grasslands their home, including the most diverse and abundant animals: arthropods! In Warren County, Virginia, Virginia Working Landscapes scientists, Smithsonian-Mason School of Conservation students and Virginia Master Naturalists swept cool-season and warm-season grass fields in search of these cool — not creepy — crawlies. Knowing which grasses provide the ideal habitat for arthropods will ultimately benefit wildlife and people, too, says VWL intern Kelsey Schoenemann.

What exactly is an arthropod?

Arthropods are a large group of animals that includes spiders, millipedes, shrimp, crabs and even extinct animals, like trilobites. This group also includes insects: arthropods with six legs, three body segments and a single pair of antennae!

Arthropods’ ancestors date all the way back to the Cambrian explosion, a period of geologic time marked by the emergence and rapid diversification of multicellular life. Their name comes from the Greek word ἄρθρον (meaning 'jointed' and 'foot'), which refers to their characteristic appearance. All arthropods are invertebrates — they lack spines — and support themselves with a durable exoskeleton; their jointed body segments and appendages enable them to move.

Why did you study arthropods?

I like studying arthropods, in part, simply because they are everywhere. This quality makes them easy to find and study. It is also easy to fall in love with them! But, more seriously, I chose to study arthropods because they are so diverse, so versatile and reflect so many life styles.

Across the globe, there are more species of insects than any other group. This variety of appearance and behavior means there is an insect for every situation. Thus, there is tremendous value in studying arthropods because they enable us to investigate the interactions between humans and life on Earth in virtually any environment.

Plus, the sheer variety of arthropods really impresses me, as well as all their unique abilities — spinning webs and cocoons, dissolving and rebuilding their bodies during metamorphosis, producing bioluminescence, navigating by scent and light cues, the list goes on. I’m always learning something new about these amazing creatures!

What benefit do arthropods provide to grassland ecosystems?

What benefits don’t they provide? As the base of the animal food chain in most situations, they directly or indirectly feed most wildlife. They are highly mobile, ubiquitous and regularly interact with plants and animals. As such, they fulfill flowering plants’ need for pollination and seed dispersal. They also control pest populations and consume living and dead organic material — like leaves, bark, fungus and carrion — which is essential for promoting the decomposition and recycling of nutrients in an ecosystem.

What were you hoping to learn?

We wanted to compare the arthropods living in two very different grassland habitat types. We conducted a pilot field season at Oxbow Farm, a hay farm that has both cool-season and warm-season grass fields with a variety of native and non-native forbs and wildflowers. Knowing how arthropods differ in cool- and warm-season grass fields across the year tells us a lot about the ability of those fields to support pollination and provide food for wildlife, among other things.

We expected these habitats to differ in an ecologically-meaningful way because cool-season and warm-season fields are structurally and compositionally very different.

Non-native, cool-season grasses — like tall fescue and Kentucky bluegrass* — grow to form dense mats with shallow roots, while native warm-season (and some native cool-season) grasses grow in bunches with deep roots. Furthermore, all cool-season grasses are dormant during the height of summer, a time when warm-season grasses grow their most robustly.

*Fun fact: Fescue and Kentucky bluegrass were originally brought over from Europe by American settlers.

How did you collect arthropod specimens?

We used a technique developed hundreds of years ago: sweep netting. Sweep nets look like butterfly nets (long wooden handle, rigid circular opening, and a tapered sock or net); the only difference is that the sweep net is made of a heavy material, like canvas. This is needed for the net to withstand our vigorous sweeping, essentially following a shallow figure eight pattern across grasses, forbs and shrubs, which knocks the bugs off the vegetation and into the net.

Just during our pilot season in 2018, we caught and counted more than 6,000 individuals!

Why did you find more arthropods in native grasslands?

Many kinds of wildflowers and forbs will flourish in the gaps between bunches of warm-season grasses, but struggle to compete for space in fields dominated by sod-forming cool-season grasses. We think that the greater variety of plant species in the warm-season field enables a greater variety of arthropods to make their living there.

Do any arthropods live in just one type of grassland?

We noticed a few families of spider that were only ever found in one field type or the other. For example, we found individuals of the Caponiidae family only in the warm season field, while Sparassidae spiders were only found in the cool-season field.

In either case, however, we counted fewer than 5 individuals, so this difference may simply be a chance outcome of a small sample size.

Ultimately, because we did not identify individuals to the species level, it is hard to tell exactly how many species the two habitat types have in common or not.

Did any of these findings surprise you?

We found much greater biomass in the cool-season grass field, which was surprising to me, initially. Upon further reflection, though, we think this result reflects the fact that cool-season grasses started growing prior to the first collection in June, while warm-season grasses didn’t get going until August.

This early boost of growth, combined with an unusually wet summer, produced lots of great food for critters like grasshoppers, which seemed to be larger and more numerous in the cool-season field.

How is this work helping to make a difference?

This study helps us to identify practical measures that will promote populations of beneficial arthropods. It looks like plant variety is important for providing food and shelter at all times of year, and that practices like mowing, grazing or pesticide spraying can directly or indirectly affect the arthropods in those fields.

Another handy aspect of this research is that it gives us a chance to talk about all the practical solutions that have already been developed. As we conduct and share this research, we use it as an opportunity to spread the word about the work that has already been done.

How do human activities affect arthropod communities?

Undoubtedly, we are impacting the planet in a profound and lasting way: virtually no places are left that do not bear some mark of human development or industry. There are numerous moral as well as economic reasons for why we should care about how our actions impact other living things. Many of these take root in the fact that we are a part of, and dependent on, the natural world, and that we cannot replicate all the services we need to survive, which are presently provided by our environment.

Thus, we can benefit from knowing how our actions, both as individuals and members of a collective, affect arthropod communities. Doing so empowers us to identify and protect the natural resources that contribute to our wellbeing. This includes activities like feeding songbirds, pollinating flowers, keeping potential pests in check and recycling organic waste.

Arthropods represent a huge, if often overlooked, part of everyday life and our choices make a difference for their continued existence.

I want to help arthropods! How do I get started?

To learn more about creating an arthropod-friendly landscape at home, check out some of these helpful resources.

Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation

Establishing Pollinator Meadows from Seed

Recommendations for meadow plantings ranging in size from a small backyard to an acre; a great resource for suburban households.

Virginia Dept. of Game and Inland Fisheries

Beyond the Bird Feeder: Attract and Support Birds with Native Plants

An article outlining how the Virginia Dept. of Game and Inland Fisheries can help readers create wildlife habitat.

Natural Resources Conservation Service

How Gardeners Can Help Pollinators

A simple landing page that describes some quick tips for pollinator-friendly gardens and provides a list of additional helpful links.

Virginia Cooperative Extension and Virginia Dept. of Game and Inland Fisheries

Habitat Gardening for Wildlife

Recommendations for creating a wildlife garden that balances beauty and utility; provides a lot of useful background information about wildlife habitat needs.

Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation

Habitat Planning for Beneficial Insects: Guidelines for Conservation Biological Control

Detailed recommendations for farmers, conservation workers or private landowners about how to design and install habitat for insects that kill crop pests.