Field Notes from Bhutan

Introduction

Three Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute scientists left in late November 2011 for the remote and mountainous Kingdom of Bhutan nestled in the Himalayas between India and China. The Smithsonian team includes the National Zoo’s chief veterinarian Suzan Murray, National Zoo veterinarian Jessica Siegal-Willott, and professional training programs manager Joe Kolowski from the Zoo’s Center for Conservation Education and Sustainability. Their mission is to conduct a critically needed training course in wildlife health and immobilization.

Descent into Paro, Bhutan. Photo courtesy of Joe Kolowski.

Bhutan

An incredibly diverse array of wildlife lives in Bhutan, much of it globally threatened or endangered. The country’s dramatic topography, which swoops from snow-covered Himalayan peaks all the way down to lowland tropical rainforest, accounts for the variety of animals that call the land home. Nearly a third of the world’s cat species, including endangered snow leopards and tigers, leopards, fishing cats, and clouded leopards. Other carnivores include Himalayan black bears, gray wolves, and dholes, highly endangered wild dogs. Bhutan is also home to endangered golden langurs, Asian elephants, takins (Bhutan’s national animal), and a many other hooved animals including musk deer, blue sheep, gaur, sambar, and muntjac.

Despite its small size, Bhutan has received international praise its protection of is natural resources. To date, Bhutan has set aside an incredible 51 percent of its land area as either protected areas or biological corridors. However, as Bhutan’s relatively small human population continues to grow and expand, people are living increasingly closer to forested and protected areas, bringing them into higher levels of contact with wildlife.

Human-Wildlife Conflict

Human-wildlife conflict issues, which include wildlife eating or damaging crops or livestock and perceived threats to human life, are on the rise in Bhutan. These issues must be addressed if the country’s ambitious conservation ethic and objectives are to succeed. The Bhutanese government plans to establish a series of wildlife rescue centers throughout the country, each manned by a team of biologists and veterinarians, trained and equipped to respond effectively to wildlife rescue and conflict situations. However, right now there is only one trained wildlife veterinarian trained to provide handle these issues in the entire country.

Solving the Problem

The seven-day intensive course, held from November 30 to December 6, 2011 in Bhutan, focuses on hands-on technical training for a combination of livestock veterinarians and forest officers in Bhutan.

The program aims to train Bhutanese scientists and managers in wildlife management tools, including safe immobilization of wild animals. Scientists hope this course will help reduce the number of animals, particularly those from endangered or endemic populations, that die as a result of limited wildlife veterinary skills, and to maximize the amount of useful data collected from animals that are either dead or handled by forest officers or biologists around the country. The course will address a range of topics, from basic animal handling and restraint to introductory animal chemical immobilization techniques, drug calculations, and safety, to guidelines for animal rescue response.

Throughout their travels in this remarkable country, the SCBI team will send reports and photos as regularly as possible, updating you on their daily activities, the progress of the training course, and the challenges and successes of this unique experience.

This collaboration with the Royal Government of Bhutan has been in the planning stages for more than a year, and was made possible by a generous grant from the Smithsonian Women’s Committee with additional support from the Bhutan Foundation.

Background

This seven-day intensive course, held from November 30 to December 6, 2011 in Bhutan, focuses on hands-on technical training for a combination of livestock veterinarians and forest officers in Bhutan.

This program, developed in collaboration with the Human Wildlife Conflict Management Section of the Department of Forests and Park Services in Bhutan, has been designed to address a critical lack of wildlife veterinary ability in Bhutan, and to increase the country’s capacity to address wildlife health and rescue situations which currently occur across a large and rugged geographic area, and decrease overall human-animal conflict.

Traditional Bhutanese roof detail. Photo courtesy of Joe Kolowski

Audience

Participants in this course will be a combination of forest rangers/officers and livestock veterinarians. There are a total of 20 geographic divisions or districts in Bhutan and approximately 8 veterinary centers. The goal is to increase the capacity within each district, or at least region, of Bhutan to respond to wildlife health scenarios by training existing veterinarians and biologists from a range of different districts with these individuals serving as the main source of knowledge for their region. The course will include 25 participants in total.

Content

This course will provide the following, with a focus on their application to bears, felids and cervids:

- An introduction to basic animal handling and restraint.

- An introduction to basic animal chemical immobilization techniques, drug calculations, and safety.

- An introduction to zoonotic disease safety, animal handling safety, and drug safety.

- An introduction to basic animal rescue response.

- Development of a collaborative network of veterinarians and biologists available for wildlife health and disease issues.

- Surveys/evaluations designed to evaluate knowledge gained by participants in the training course and identify needs for future training.

Location

The majority of the course will be spent at the Ugyen Wangchuck Institute for Conservation and Environment (UWICE) in Bhumtang, Bhutan. A portion of the course will be spent in Thimphu, utilizing the facilities and animals at the Animal/Livestock Research Center and the Bhutan Takin Preserve.

Field Notes from Bhutan

Field Note 5

The return drive to Thimphu from Bhumtang, across half of Bhutan, was even more spectacular than the first time. We were treated to stunning views of the snow-covered Himalayas, which were obscured by clouds on our drive to Bhumtang. On top of that, we had a fantastic sighting of a group of gray langurs with at least one small juvenile making their way through the tops of moss-covered trees on the slope beneath the road.

The Himalayas. Photo courtesy of Joe Kolowski.

Later in the evening we were given some disappointing news: We would be unable to immobilize semi-captive deer with the participants as planned due to unforeseen changes in the locations of the candidate individuals in the preserve. Although the course participants shared our disappointment, we made the best of our visit the Bhutan Takin Preserve, which contains 14 semi-captive takin, mostly rescued from various situations in the wild, in addition to some northern red muntjac (barking deer) and sambar deer, all beautiful animals that I had never seen before in the wild or captivity. The sambar deer were particularly impressive due to their immense size alone. We spent the morning discussing situational awareness and preparations that would have been necessary if we did conduct immobilizations in the various-sized fenced areas of the preserve and spent time discussing specific darting scenarios. It was not the morning we had planned, but an excellent learning opportunity nonetheless.

Sambar deer buck and doe (left) and takin (right) at the Bhutan Takin Preserve. Photos courtesy of Joe Kolowski.

In the absence of working directly with animals, we spent the afternoon reviewing the course with the participants and discussing what they felt should be the priorities and next steps in continuing with this type of training in Bhutan. It was important for us to get their perspectives on how best to ensure this training continues to be built upon and developed. In the late afternoon, we held a formal closing of the course, where participants were given their course completion certificates by Suzan Murray, and Karma Dukpa, the director of the Department of Forests and Park Services. Karma Dukpa is one of the most senior government officials working in the field of conservation within Bhutan, and we were very happy to have him preside over the course closing.

Before distributing the certificates, Karma Dukpa spoke passionately about how important this effort is within Bhutan to increase their national capacity for dealing with wildlife rescue and conflict situations. He talked of an incident when he was stationed in Bhumtang years ago, based at UWICE itself, which was previously the headquarters of the Forestry Department. A large male Himalayan black bear was trapped by his forearm in a barbed-wire fence. He talked of how the bear suffered needlessly and how they had no choice but to shoot him, knowing nothing of immobilization, and having no other tools or equipment at their disposal. He talked of the Buddhist teaching that animals, like humans, deserve happiness and a life free from undue suffering. The incident clearly had an effect on him, and reinforced the importance of this training course.

Finally, we formally handed over five wildlife rescue kits, which included specialized wildlife veterinary equipment difficult to obtain in Bhutan, yet necessary for safe and effective handling and immobilization of wildlife, including darting pistols and dart syringes, bite gloves, and pulse oximeters, which monitor pulse and blood oxygen levels of sedated animals. These kits were an important component to the country’s vision for increasing capacity in this field, as their wildlife rescue efforts have been impaired not only by a lack of personnel, but also by an inability to get the necessary field equipment.

Presenting the five wildlife rescue kits. Photo courtesy of Joe Kolowski.

We were graciously invited to join everyone for a closing dinner that night, and were treated to a huge, delicious buffet of traditional Bhutanese food. It was one of the best meals of the trip to be sure, and after dinner many crowded around the TV to watch Bhutan’s national soccer team lose five to zero to India. Apparently, Bhutan did better than expected in this matchup and all were relatively pleased with Bhutan’s performance.

Saying our goodbyes to the course participants, it became clear that the course meant a lot to many of them professionally and personally, that they felt they had learned a lot, and that they had deeply enjoyed the experience. I know that was certainly the case for our team as well.

Field Note 4

We wake up to yet more sunshine on the fourth day of the course and begin the day with a review of drug dosage calculations, one of the most important topics for participants to understand if they are to find themselves involved in darting procedures in the future. Fortunately, the group seems to have no trouble with the calculations, and we move on to practice with the dart syringes.

The darts used for immobilizations are clever little devices, where air is applied to a chamber in the back of the syringe, pressing against the syringe plunger. Only a small rubber sleeve prevents the loaded drug liquid from shooting out of two holes in the side of the syringe, and this sleeve is released from its position by the skin of the animal once the dart makes contact, thereby delivering the dosage.

We spend a couple of hours teaching how to ensure the darts are working properly, and how to load and “arm” the syringes. This is one of the first “hands-on” opportunities of the course, and it seems the participants are happy to get a break from lecture and get their hands on some equipment. After a few rounds of practice, and a few mistakes, the groups seems to catch on well and we break for lunch.

Practicing with the blowpipe. Photo courtesy of Joe Kolowski.

The rest of the afternoon is spent letting the participants practice with the dart delivery systems themselves, and for this we’ve brought a blowpipe, best for short distances, and an air pistol, accurate (with practice) to more than 25 meters. It certainly takes practice to fine tune the air pressure and aim necessary to hit your target consistently, but the group had plenty of fun giving it a try. Over the course of the afternoon, some certainly emerged as particularly skilled shooters, but it seemed like everyone enjoyed the practical experience, and the chance to get familiar with the new equipment. Overall it was great opportunity for everyone to interact on a more social, less formal level, celebrating the bulls-eyes, and the misses as a group. Of course, before darting an actual animal, many hours of practice are required, but this was a good way to let them know what the process would be like, what the factors are that need to be considered, and how the equipment works.

That night I had the opportunity to walk around the town of Bhumtang, where the training center is located and get a feel for the area, its architecture and layout, and the people that live there. I learned that the town actually burned to the ground less than six months ago, and that what we were seeing was a new town built on top of the charred remains. Given the number of buildings, and their size and level of detail, it was incredible to think the town was leveled so recently. And apparently it was not the first time fire had destroyed the town.

In any case, we packed last night after sharing dinner with much of the staff of UWICE at our guest house. This morning we head back to Thimphu (by way of the eight to ten hour drive again), and tomorrow we hope to get the participants some hands-on experience with semi-captive animals at the Bhutan Takin Preserve. However, just yesterday we were told that our plans to assist with some procedures on barking deer or sambar deer may be cancelled. We’ll have to confirm this evening when we get to Thimphu, but hopefully that’s not the case.

Loading the syringe and practicing with the blowpipe. Photos courtesy of Joe Kolowski.

Field Note 3

The Director of UWICE, Nawang Norbu, was kind enough to welcome us and the participants to the course and start things off. Nawang actually attended one of our professional training courses in Front Royal, Virgina this past year, so it was great to see him again and catch up with him a bit that morning. Following that, we all went around the room and introduced ourselves. For the introductions of the participants, I projected a map of Bhutan with its 20 districts, so that we could see where everyone was working. We were happy to see that the participants had come from a diverse range of regions and parks of Bhutan, as was our hope, and it was a good way for us to begin to get more familiar with the geography of Bhutan. We had also asked everyone to talk briefly about what they hoped to get out of the course, and we were all encouraged that their hopes seem to align well with what we had planned for the week. Based just on their introductions, they also seemed like a thoughtful, kind, and enthusiastic group, which was certainly encouraging.

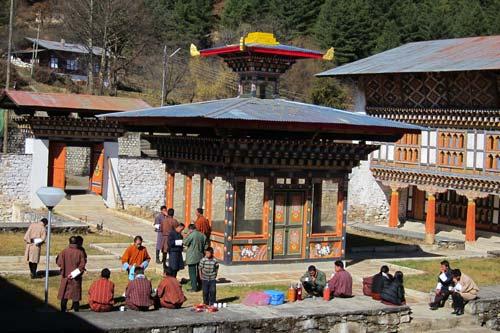

After an overview of the week ahead, we began the day’s lectures. Day one focused on animal and human safety when handling wild species, and introduced regional zoonotic diseases (those that can be passed from wildlife to humans) to be considered. During this first day we were also introduced to the tea break, which would occur twice a day throughout the course, without fail. We took the break out in the courtyard and it included both tea and coffee as well as butter tea, which I’m told (and confirmed!) is an acquired taste. Although the tea break on this first day was quite cold, the coming days were sunnier, and we came to look forward to this chance to soak in the sun, warm up, and get to know the participants a bit better. Aside from the cold temperatures and some power outages, the first day was certainly a success, and it felt great to finally get the course underway.

The courtyard, where twice-daily tea breaks occurred. Photo courtesy of Joe Kolowski.

At the conclusion of the first day we were invited to an opening dinner celebration later that evening at the dining hall. A roaring fire was prepared in the fireplace and a huge spread of local Bhutanese fare was provided including the most popular local dish “chili cheese”, which is a creamy cheesy broth filled with nothing but spicy green peppers, served over rice. Although it was great to socialize with the participants, and even sample some of the regional beers and Bhutanese whiskey (the malt comes from Scotland), all three of us were struggling to stay awake, still not adjusted to the 12-hour time difference, and we retired fairly early.

Using the pulse oximeter. Photo courtesy of Joe Kolowski.

Days two and three of the course focused on the specifics of anesthesia and handling of deer, bears, and felids, the groups that we would focus on throughout the course. Lectures dealt with the details of deciding between manual and chemical immobilization, identifying the appropriate drug combinations and dosages for animals of different species and sizes, and introducing some of the darting equipment, such as the blowgun and air pistols as well as monitoring equipment like the pulse oximeter. The participants responded well to these lectures and there was a lot of active discussion about these topics.

This morning we were treated to a rare sight on the way to UWICE, four black-necked cranes flying high overhead. The species, which is listed as vulnerable to extinction by the IUCN, is highly regarded in Bhutan, and a festival in the country celebrates the species every year. Suzan had been hoping to get a glimpse of these beautiful birds during our trip so she was particularly excited. This evening, we are preparing for our last day of lectures here at UWICE, which will focus on darting protocols and practice with some of the equipment. As with every night here at the guest house, I’m focused on keeping the wood stove well fed to fight off the outside cold. We’ve been treated to two sunny days in a row and we’re hoping for more of that tomorrow.

Field Note 2

Our driver met us at 7:30 a.m. at our hotel, we packed our equipment and luggage and were off. Almost immediately the road began climbing and it became clear that a straight stretch of road would be a rare experience indeed for the rest of the day.

This first climb seemed to last close to an hour and by the time we crested the mountain, we were surrounded by a thick fog with almost no visibility. At the crest, at least twenty or thirty lines of prayer flags stretched across the road and a traditional Buddhist “Chorten” (a religious memorial structure that can take on various meanings) marked the peak, which was still surrounded with evergreen forest. The flags and religious structure were particularly eerie in the surrounding fog.

Over the course of the next ten hours we would crest at least two more mountaintops with some descents and climbs lasting more than two hours. Each valley was markedly different from the last, either in topography, vegetation or both. Between each successive climb we would cross another clear mountain river, often passing through a small town, yet the vast majority of the drive was characterized by dense forest, both deciduous and evergreen.

Although we didn’t expect any wildlife sightings on the drive, we were treated to a few. We saw two groups of Assam macaques near the road, as well as a single gray langur, a long-tailed furry monkey with a dark black face.

Not only was the road winding, it was narrow. Indeed, in some places had to stop the truck completely to allow a larger vehicle to safely, slowly squeeze by. Despite the length and at times treacherous nature of the drive, it did allow us to become familiar with this incredible landscape, along with Bhutan’s distinctive house architecture, which is characterized by the relatively large size of the often square structures, the intricate carved detail in the window frames, and framing below the roof, and of course, the color. We crossed three of Bhutan’s 20 districts on the drive. Each district includes a dzong, a large imposing monastery-like building, often built on a precipice or hilltop, which houses the primary administrative offices of the district as well as a community of Buddhist monks. These structures were some of the most impressive we’ve encountered so far.

Drive through Bhutan. Photo courtesy of Joe Kolowski.

We arrived after dark to our guest house in the town of Bhumtang, and quickly got fires going in the wood stoves in each of our rooms as the temperatures were below 50 degrees already. After a delicious dinner of traditional Bhutanese fare, we retired to our rooms to prepare for the following day’s lectures.

After a four-kilometer drive up the mountain which passed Bhumtang’s impressive Dzong, we were treated to a view of the main building that houses the classrooms and offices of the Ugyen Wangchuck Institute for Conservation and Environment where most of our course would be held. It is a remarkable structure built in the late 1800s, which served as the palace of the first king of Bhutan, Ugyen Wangchuck. Although showing its age, the building has been renovated and maintained well over the years. With much of its original woodwork and stone, the building is impressive and beautifully constructed, with a striking view of the countryside below.

As we sit in the buildings offices preparing for the coming day, we’re all excited to begin the course after so much preparation, and meet the 25 participants with whom we’ll be spending the week.

Ugyen Wangchuck Institute for Conservation and Environment. Photo courtesy of Joe Kolowski.

Field Note 1

Traveling to Bhutan is a time-consuming affair. The first leg of the journey is a 15-hour flight from Dulles Airport to Narita Airport in Tokyo, Japan where we transferred planes and began our second leg, a seven-hour flight to Bangkok, Thailand. Much closer to our destination, but many miles remained. A late-night arrival and an early morning departure for our next flight forced us to overnight in the airport, which was characterized by a notable lack of comfortable chairs. We were surprisingly anxious to board the next flight five hours later, despite already logging 22 hours in the air. Our final leg was a three-and-a-half hour flight to Paro, Bhutan which included a brief stop in Guwahati, India.

Snow-capped mountains of the Himalayas entered into view as we approached Bhutan. For the last couple minutes of the flight we were treated to a uniquely close view of the rugged mountainous landscape around Paro. To land in this terrain, the airliner must make a series of steep banking maneuvers at low altitude and at times we seemed shockingly close to the valley walls and the houses dotted along them. The landing at Paro is considered one of the most difficult in the world, and it did not disappoint.

Drive through Bhutan. Photo courtesy of Joe Kolowski.

We needed nine plastic crates of various sizes to transport the specialized supplies and equipment needed for the course, some of which will be left in Bhutan so that skills learned during our course can be implemented effectively in the field. Adding in our own personal luggage, this meant we would be traveling for the next three days with 12 different pieces of luggage. Fortunately our team and our Bhutanese colleagues worked hard to get all the proper paperwork, ensuring that at least passing through customs in Bhutan would be relatively painless.

Our journey, at least for today, ended in Thimphu, the capital, which is a breathtaking one-hour drive alongside crystal clear mountain rivers. Tomorrow we continue our journey with a ten-hour drive, which will conclude in the town of Bhumtang, at the Ugyen Wangchuck Institute for Conservation and Environment, one of our main partners in the course and the site of most of the training program. The length of the upcoming drive after such a long journey is a bit daunting, but we are all excited to get an extended tour of the Bhutanese landscape. After meeting briefly with some of our Bhutanese colleagues we retired to our rooms to get some much needed sleep.