Featured Creature: Black-Footed Ferrets

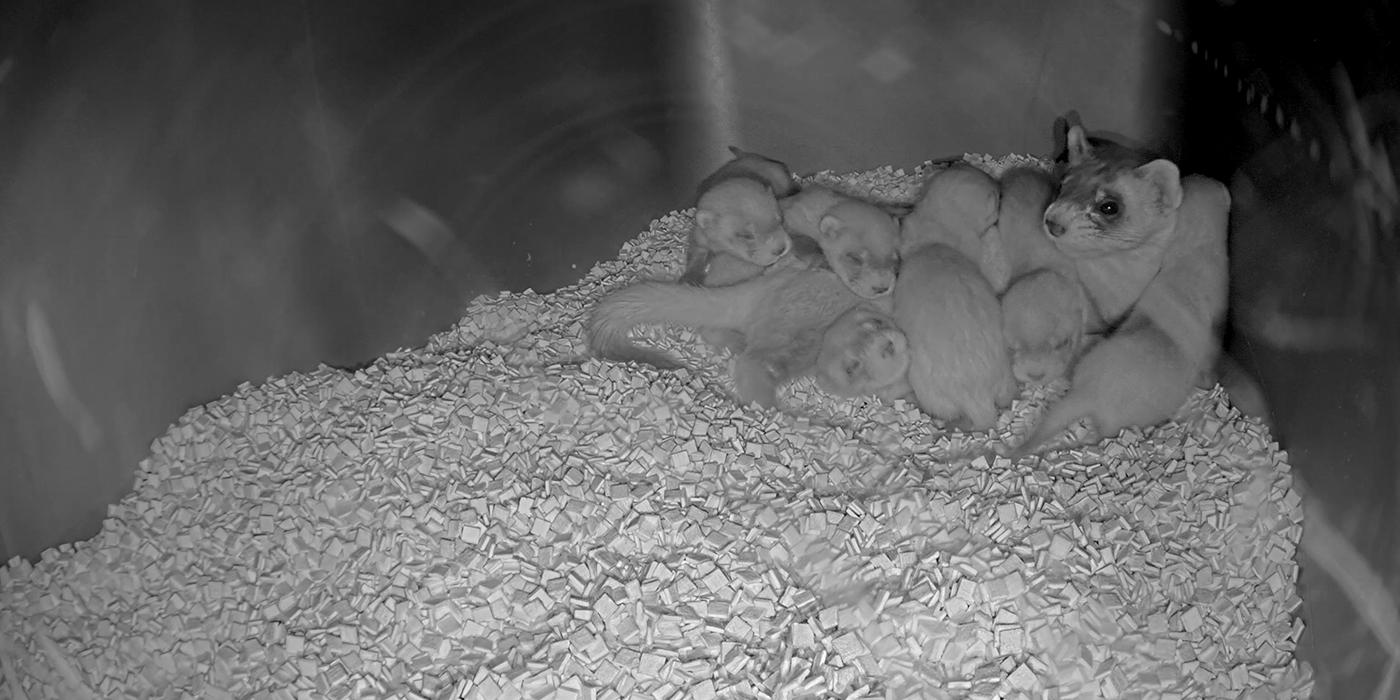

If you have watched our black-footed ferret mom Potpie and her six kits on our Kit Cam, then you likely know their backstory. Potpie kicked off whelping season May 10 here at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) in Front Royal, Virginia. Her timing couldn’t have been more perfect—Mother’s Day! Since that date, we have welcomed 49 surviving kits this breeding season.

Potpie is an experienced mother, and it is clear that she is a very devoted and caring mom to her two sons and four daughters. Ever since the kits were born, we, like you, have been glued to our screens. For the first few days of the kits’ lives, we allowed Potpie to bond with her offspring without any interruptions from us. There was no need for us to intervene since she was caring for them, and all appeared to nurse and grow as expected.

On May 20, 10 days after the kits were born, we did a quick health assessment. At that age, the kits’ hair is quite thin, but it grows quickly. Therefore, identifying them with shave marks—as we do with the cheetah cubs—would not be an effective strategy for identifying them. Although we were not able to tell exactly who was who, we wanted to obtain base weights on the kits to ensure they were gaining steadily and that no one was falling behind their littermates, size-wise.

At 10 days old, kits tend to weigh between 30 and 50 grams, depending on the individual, mom and litter size. Our two male kits were the largest (51.5 grams) and smallest (36.5 grams) of the litter. Their sisters were all relatively close in weight and ranged between 40.5 grams and 43.5 grams. We were happy to see that they were right on par!

By the time the kits turned one month old, their distinctive “mask” facial markings and the dark fur on their feet began to show. In addition to nursing, the kits also began eating meat. Some observant Kit Cam watchers noticed that Potpie would cache her rats in the nest box, then eat when she was hungry. Around the one month mark, the kits began sampling some of her diet.

They had also become quite active in the box! It was not uncommon to see the kits playfight with each other. They bite, wrestle and thrash around. These types of play mimic how they hunt prey and allows them to hone their skills safely.

Around 5 or 6 weeks old, the kits’ eyes began to open. Generally, most littermates will open their eyes within a few days of each other. Interestingly, they don’t necessarily open both eyes at the same time. Some individuals opened one eye a day or two before the other. This is a normal occurrence. They appear to be perpetually winking, and it is adorable!

This week, the kits have crossed the 7-week-old mark, which means that they’re ready to try hunting live prey. All of the black-footed ferret kits and adults at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute have the potential to be reintroduced to the American prairie, so fine-tuning these predatory behavior skills will be key to their survival should they be selected for the reintroduction program.

In the wild, 90 percent of black-footed ferrets' diet consists of prairie dogs. Food requirements vary with the seasons and among individual ferrets, but they generally consume one prairie dog every three or four days. Ferrets have a high metabolic rate and require large quantities of food in proportion to their body size. One ferret may eat over 100 prairie dogs in a year, and scientists calculate that one ferret family consumes more than 250 prairie dogs each year. The remainder of their diet includes mice, rats, ground squirrels, rabbits, birds and occasionally reptiles and insects.

Black-footed ferrets use a loud "chatter" to sound an alarm.

Since we cannot feed prairie dogs to our black-footed ferrets, we give them the next best thing, nutritionally speaking: live rats. In addition to helping the kits sharpen their hunting skills, feeding whole prey also helps maintain good dental health. Gnawing on bones and fur cleans the ferrets’ teeth and prevents gingivitis.

In August, scientists will conduct a genetic assessment of the entire black-footed ferret population managed in human care. This assessment will determine whether the kits remain at SCBI, are transferred to another breeding facility or join the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service pre-conditioning program in preparation for their release into the wild.

Kits naturally separate from their mother around four months of age, so as their behavior dictates we will mimic that natural behavior. Meantime, we hope you enjoy watching our little black-footed ferret family as they bond, play and share a meal with one another.

This story appears in the July 2020 issue of National Zoo News.

Related Species: