A Day in the Life of a Bird House Keeper

Caring for many bird species—from the itty bitty indigo bunting to the giant greater rhea—is all in a day’s work for Bird House keepers at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo. Although renovations to transform the building into the brand new Experience Migration exhibit are well underway, keepers are hard at work behind the scenes. Assistant curator Eric Slovak gives a sneak peek into a day in the life of a Bird House keeper, from training animals, to monitoring their health, to providing them with engaging and enriching habitats and much more!

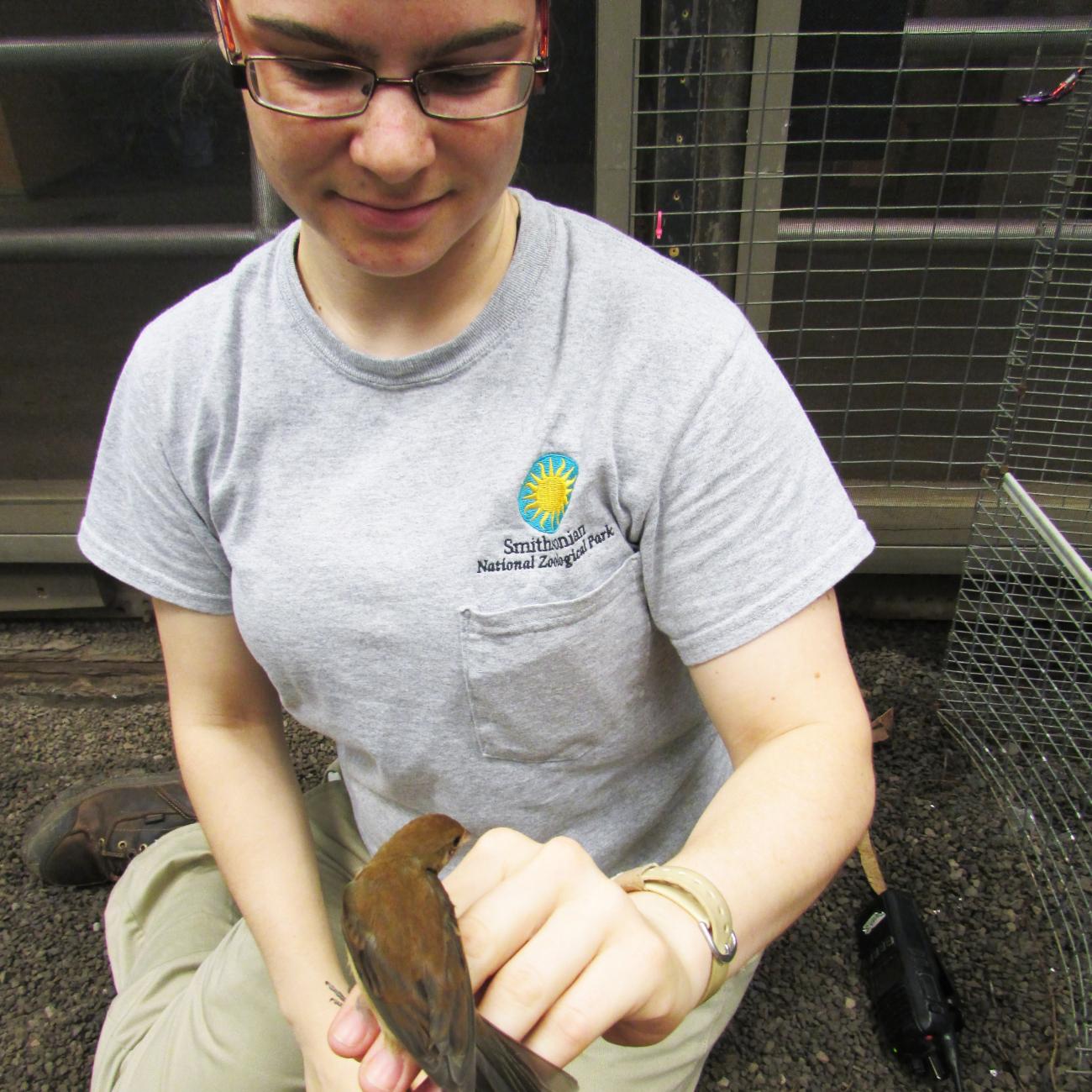

The condition of a bird’s feathers can offer keepers a window into their health and well-being. Performing a hands-on exam is a good way to get a close look at them. Holding large birds like parrots and owls can take bravery. Holding woodpeckers can require steely resolve because they try to peck at your hand! And, holding a tiny ruby-throated hummingbird, like this one in animal keeper Liz Fisher’s hand, requires a light, delicate touch.

Our birds receive frequent check-ups from the Zoo’s veterinarians, but animal keepers are on the front lines of monitoring the birds’ daily health. Since feathers obscure birds’ bodies, it is difficult to observe visually if a bird is gaining or losing weight. Instead, we rely on positive reinforcement training to get weekly or monthly weights on them. In this photo, animal keeper Heather Anderson is coaxing a black-crowned night heron onto a scale in its enclosure. A main component of positive reinforcement training is choice; the heron can choose to voluntarily climb on the scale or walk away. If he chooses to participate, Heather rewards him with a treat. If not, she will try the training at another time when he is in the mood to participate.

Kiwi eggs are cause for celebration at the Zoo and Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. These birds are critically endangered in their native New Zealand, and breeding them in human care can be a challenge. This species is unique in that males incubate and guard the eggs. The technique of candling, as animal keeper Kathy Brader demonstrates in this photo, helps us check for fertility and monitor chick development.

What does a keeper do when a really big bird needs to move into a new habitat? Why, walk with her and a few friends, of course! Greater rheas can stand three-to-six-feet-tall and weigh 33 to 66 pounds. In this photo, keepers walk a female rhea to her new exhibit. We hold up sheets of plywood around her to protect her and prevent her from being spooked.

Prior to the Bird House’s closure for renovations, a big part of our keepers’ day was sharing their animal knowledge with Zoo visitors. In this photo, animal keepers Heather Anderson and Ric Pinto host a Meet A Flamingo demonstration in summer 2016. Once Experience Migration opens in 2021, visitors will once again be able to meet bird keepers and learn all about the fascinating and diverse migratory bird species in our care!

Breaking into the zoo-keeping field can be challenging. Some people seek careers in the animal care field, while others want to donate their time and effort to a cause they feel passionate about. Animal keepers Gwen Cooper and Jordana Todd run the volunteer and internship program at the Bird House. Shown here with intern Megan Henning (center), Gwen and Jordana help mentor and train the future generation of keepers and keeper aides.

Some baby birds can be quite big! Animal keeper Debi Talbott holds a juvenile Stanley crane right before a veterinary exam. When young, these birds have golden-red feathers on top of their heads. As they grow and molt their feathers, these cranes get a beautiful silvery-blue head that is both sleek and elegant.

We work closely with birds, like Mac the green-winged macaw, to gain and maintain their trust. Animal keeper Liz Fisher provides Mac with lots of attention, enrichment and training to keep him physically and mentally active throughout the day. In particular, he seems to enjoy listening to the radio; he appears to sing and dance while keepers tend to the other birds in the aviary!

Animal keepers can sometimes determine the sex of a baby bird before they hatch! Assistant curator Eric Slovak makes a tiny hole inside this greater rhea egg and extracts a small bit of DNA. A dab of epoxy is used to seal the hole as though it was never there. He sends the sample to a DNA sexing lab for analysis. In a weeks’ time, animal keepers will learn the sex of the bird inside the egg!

Animal keeper Sarah Steele holds a female indigo bunting, one of the many songbirds at the Bird House that are native to North America. Unfortunately, some migratory songbird populations are declining. To understand the challenges migratory birds face, our colleagues at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center are gathering data by tagging and GPS-tracking the birds. From Kirtland’s warbler and gray catbird migrations, they have been able to see and piece together the ways climate change and manmade changes to landscapes are affecting a variety of species.

Meanwhile, over at the Bird House, keepers go to great lengths to study husbandry and breeding habits of indigo buntings and other native species. Birds’ needs and wants change with the seasons, so keepers must be flexible; they may need to adjust care at a moment’s notice! The information we learn about these species may help answer some of our scientists’ questions and help us conserve these birds and their native habitats.

This story appears in the December 2017 issue of National Zoo News. Enrichment and training allows animals to demonstrate their species-typical behavior, gives them opportunity to exercise control or choice over their environment and enhances their well-being. Learn more about the Zoo’s Animal Enrichment and Training Program.