A Day in the Life of an Amazonia Keeper

Dive into the Smithsonian’s National Zoo’s Amazonia exhibit and discover fish that zap their prey using high-voltage electricity, a titi monkey and birds roaming freely through the flooded forest, and a coral reef where clownfish deftly dart through the tentacles of anemones. Caring for creatures that live in the sea, on land and in the sky is a fun challenge for the dedicated team of animal keepers. Go behind the scenes to learn how they provide enriching environments and experiences for the animals in their care.

Titi Monkey Training Session

“Our male titi monkey, Henderson, is very curious, which makes him a great animal to work with. One of the ways that we monitor his health is by conducting husbandry training sessions inside the forest. Because the exhibit is open and the animals roam freely, we want him to be familiar and comfortable with coming to a designated spot voluntarily. To communicate with him, we use a target stick with a blue ball on the end. When he sees that target, he knows that he should follow it and touch his nose to the ball. If he does, he receives a reward from me, usually in the form of peanuts, grapes or—as is the case today—a bright red strawberry. We do these sessions with him at least twice a day both to reinforce these behaviors and so that he has an opportunity to socialize and bond with us.”—Donna Stockton, animal keeper

Bird Recall Training

“Our rainforest is quite big, so in order to ensure that all 13 of our birds are healthy and accounted for, we do recall training sessions every morning. To cue them to come to us, we hit a wood block five times; that signals to them that breakfast is served at the food pan! At this time, we offer the birds food items that they really enjoy, such as grapes, banana, meal worms and wax worms. By only offering them these ‘high value’ rewards, it encourages them to come into the enclosure for those delicious goodies. That allows the keeper to make sure that everyone is in good condition and monitor any competition between individuals or pairs. It is also a good indicator to us if somebody does not show up at the food pan that they may be ill. Or, if a pair doesn’t show up, it could mean that nesting season has begun, and they’re sitting on eggs! We have a checklist that helps us track who is coming to the food pan. We want them to get comfortable entering and exiting the enclosure in the event they need a vet exam.”—Hilary Colton, animal keeper

Pacu Medical Exam

“On occasion, we will need to do an exam or perform surgery on one of our fish. Doing so requires us to put anesthesia in the water. Zoo veterinarians wanted to check this pacu’s cholesterol levels.”—Hilary Colton, animal keeper

Testing Tank Temperatures

“When we arrive in the morning, one of the first things we do is check the temperature of the tanks to ensure that they are between 78 and 84 degrees Fahrenheit. If they are too low or too high, they could affect the health of our fish and turtles. We want to make sure everyone is comfortable in their habitats.”—Lando McCall, animal keeper

Feeding the Reef

“Every coral eats differently. Stony corals are the reef builders, and most of them are photosynthetic—they filter phytoplankton and zooplankton out of the water, but mostly they rely on their symbiotic algae for food. Hard corals, like our elegance coral, receive finely minced fish, shrimp and clams every Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. The tentacles work together to catch the food and have stinging cells, called nematocysts. When a fish, shrimp or plankton brushes close to them, they sting them and catch their prey. The tentacles have barbs, which hook the prey and pull them inside the mouth. The crabs that share their tank help by eating the coral’s leftovers!”—Thomas Wippenbeck, animal keeper

Fun with Food Enrichment

“These are driftwood feeders for our fish pools. On today’s menu are carrots, zucchini and romaine lettuce. We put these enrichment feeders into our pool with our smaller fish who eat roots and plant leaves from the river banks. By presenting their diet in this way, they can forage in a similar way to how they would in the wild. All of these food items typically float, so by tying them to a piece of driftwood, they will sink and make the fish feeding visible for our visitors. It also lets me get a good look at the animals when they come up to the glass to make sure nobody has any scrapes or injuries.”—Hilary Colton, animal keeper

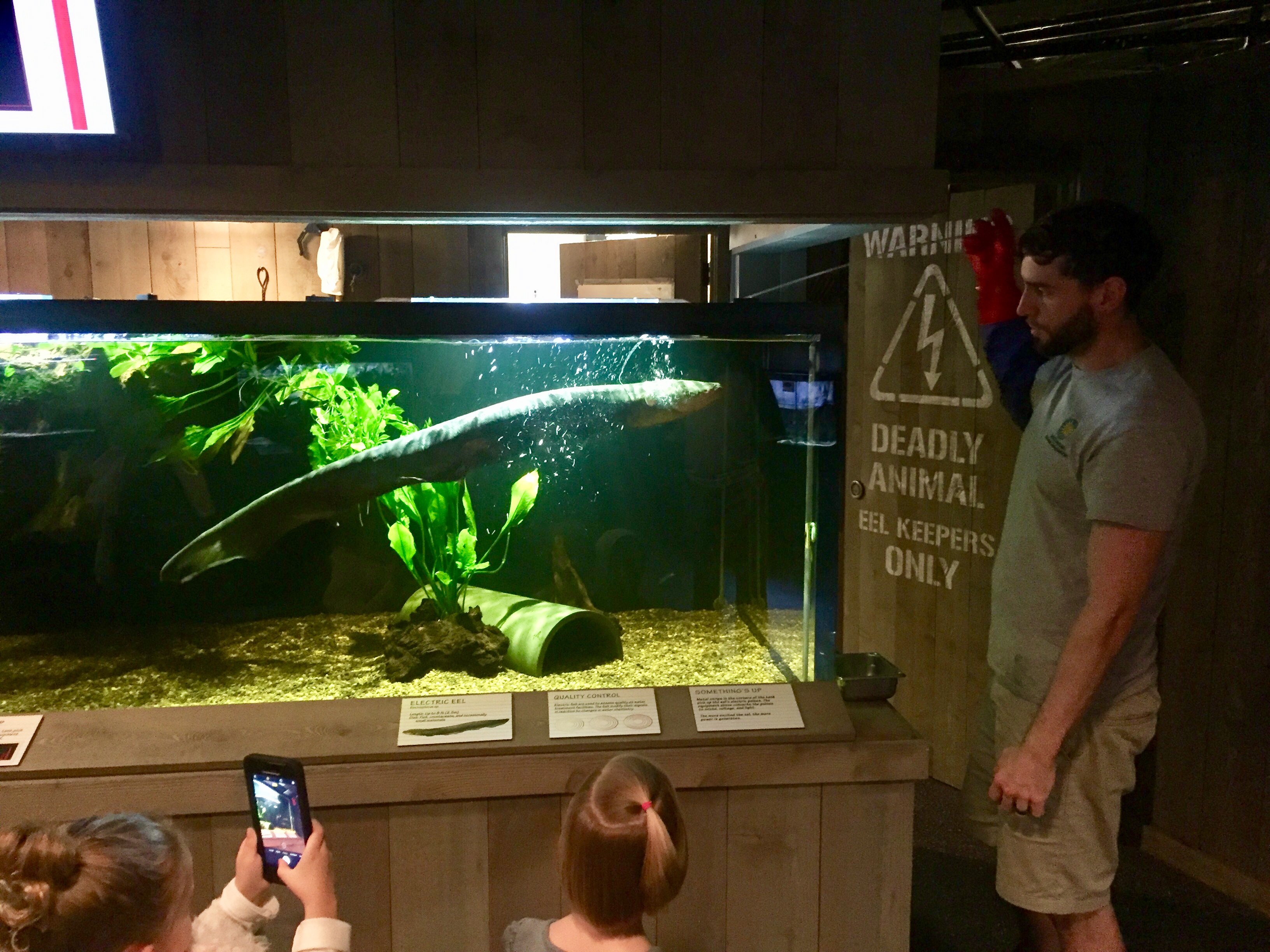

It's Eel-ectric

“Electric eels use the Sachs electric organ and Hunter’s electric organ to stun and catch their prey. It’s like a battery; the eel’s head has a positive charge, and the tail has a negative charge. They only use the charge for hunting or to defend themselves. Most eels send about 600 volts surging through the water, but others have been recorded going up to 860 volts! Safety is always top of mind whenever we have to interact with our electric eel, so we wear protective rubber gloves and use a plastic feeding stick to pass her fish, shrimp, crustaceans and worms. Visitors can watch her eat during the 1 p.m. demonstration and see her voltage register on the screen above her exhibit.”—Denny Charlton, animal keeper

Breakfast at the Zoo

“The Zoo’s Department of Nutrition Sciences delivers diets daily to Amazonia for our birds and our mammals. Each comes in its own container and is labeled for morning or afternoon. Some species, like our birds, get one diet throughout the day. We place multiple pans throughout the forest so nobody develops a territory in one spot. The spoonbills get a mixture of a duck food and flamingo diet, which gives them their pink coloration. Our titi monkey, Henderson, gets his salad in the morning and his fruit in the afternoon. We find that he does not want to eat salad after he’s been offered fruit first. Howie, our sloth, gets a salad of root vegetables, squash, corn and greens. Sometimes, he will eat kale, although it is not his favorite. He also receives a small amount of fruit; the fruits in the rainforest are lower in sugar than the ones we are accustomed to. So, he receives beets, sweet potatoes and carrots rather than a big piece of papaya.”—Hilary Colton, animal keeper

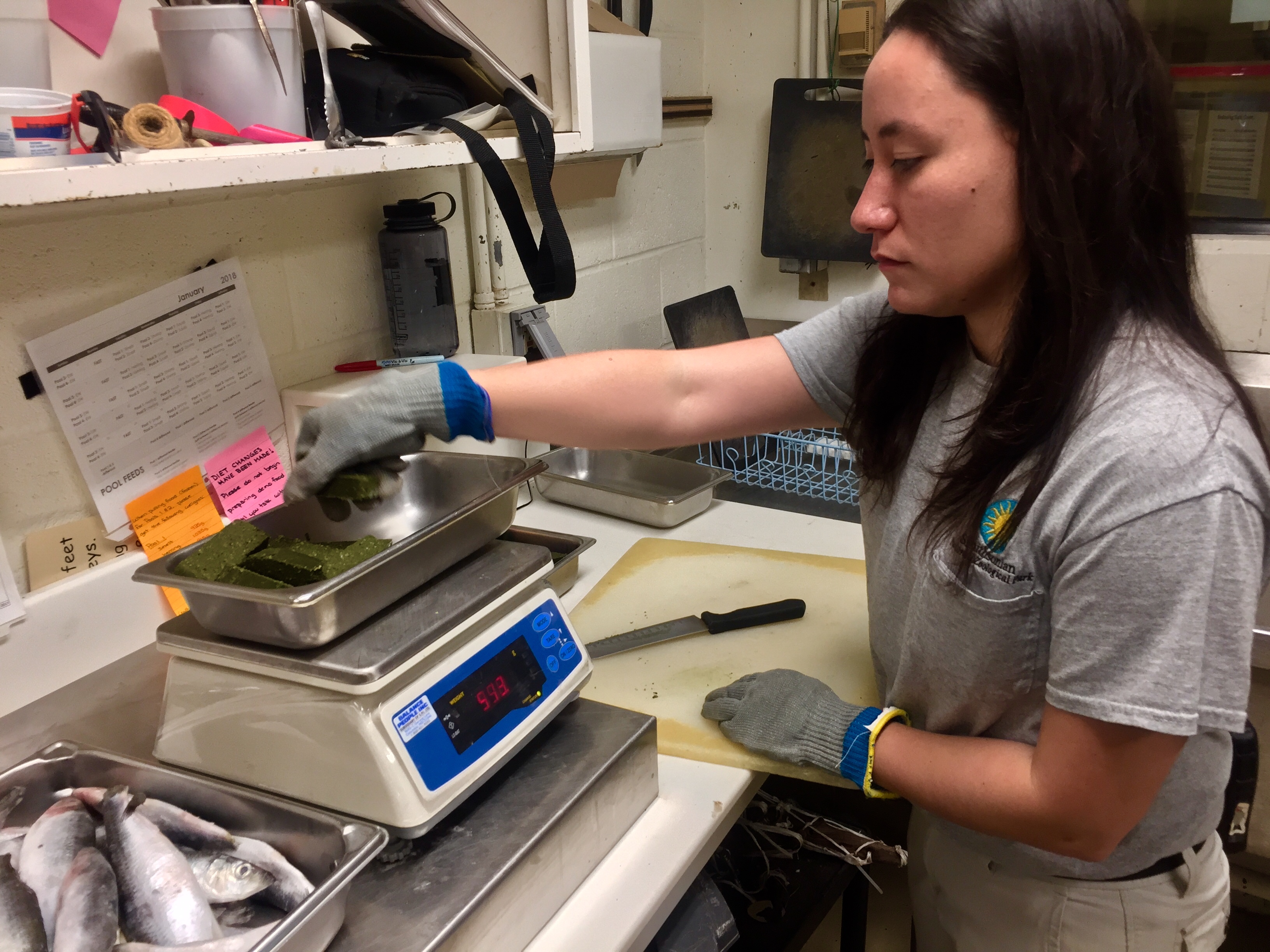

Feeding with the Fishes

“The arapaima are our biggest fish at Amazonia. Our largest one measures just over 6 feet in length; we estimate him to be anywhere from 250 to 275 pounds. The pacu are a rounder fish that are adapted to eat fruits and nuts, and they are around 3 feet in length and 65 pounds. Per our veterinarian and nutritionist staff, the pacu have been deemed slightly on the pudgy side, so we have put them on a diet. The arapaima are fed the higher fat omnivore gel, which we can cut into larger pieces and spot feed to them. The pacu are getting the vegetable herbivore gel, which has a lower fat content. The arapaima sit and lurk at the water’s surface waiting for prey items, so we can see individuals and toss them the larger pieces of omnivore gel to ensure that at least 2 or 3 slices are going to each fish. The arapaimas also get about 730 grams of meat; we alternate feeding them herring, live earthworms, smelt, squid and shrimp. All of our fish is delivered frozen, so we thaw them out overnight and prepare them in the morning. The food on the menu depends on what items we can source sustainably at a given time.”—Hilary Colton, animal keeper

This story was featured in the March 2018 issue of National Zoo News. Visit Amazonia at 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. to chat with keepers and see a fish feeding demonstration.